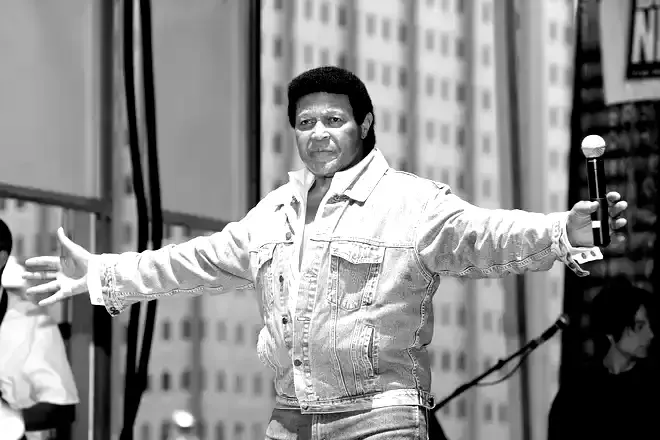

The Power of Rothya James' Short Stories

Explore a collection of captivating short stories written by Rothya James that skillfully delve into his personal life experiences and convey significant moments through compelling narratives leaving a lasting impact on the reader's mind. Each story is a treasure trove of emotions, filled with intricate details and vivid imagery that will transport you to different times and places.

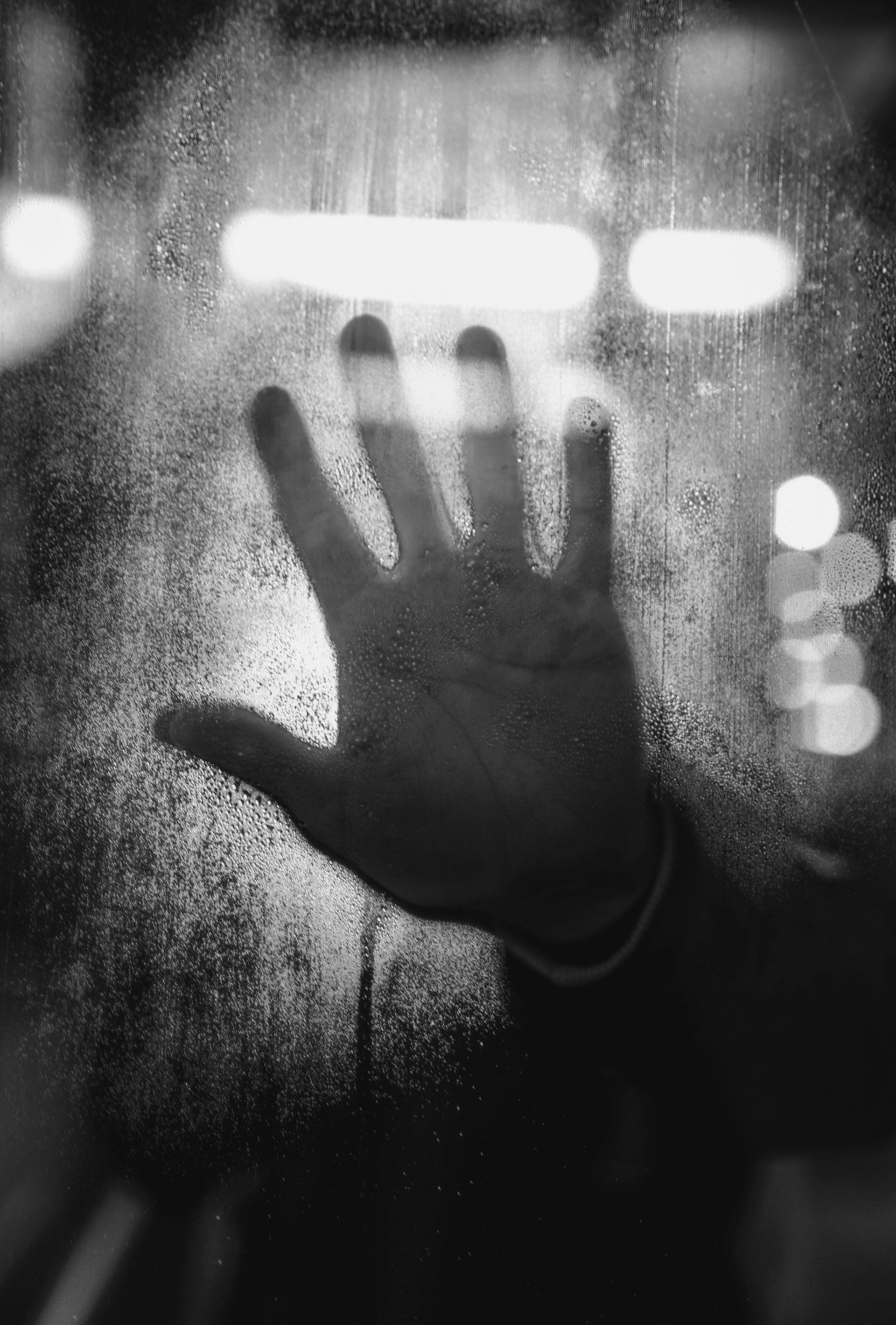

Falling for Love by Rothya James I can hear the wind whistle through my hair. The force of the rushing air distorts my face into a silly grin and create slits for eyes to tear from. I’m free as a bird and on my way to find my girl. It will be a long and solitary journey, but the end result is the true love of my life. I can’t wait. It all started when I lost my Mary. I always thought such a common name for the extraordinary woman she was made the whole match an oxymoron. She was beautiful. Raven blue-black hair cascading around cat-like green eyes that could be taken for emerald gems. Her eyes were set above a delicate straight nose and a small cleft in a strong chin. She had clear porcelain skin with the slightest hint of blue veins along the lean parts of her body. They looked like faint tiny rivers, and I spent many hours running my hands along the undercurrents of that snow-white, pillow-soft texture. With an hourglass figure exposing hips that outlined the small of her waist and a length to her legs that made her five-eight frame seem taller than she was, she caused a vision one would swear belong to a Greek Goddess. Her breasts were full and firm with silver dollar nipples painted in a dark brown tone. The contrast of her nipples to her skin equaled the contrast her raven black hair made. Nude, she was mesmerizing. Not from this world. She was a genuine dream come true, and the best part of it all was that she loved me. I loved her too. There were countless reasons to love her. The crooked little smile that always appeared after a quirky observation; she had a long, slow curve at the nape of her neck where I lingered with numerous kisses. There was an impetuous glint in her eye that would build when she wanted to make love. Her laugh would sing in your ear and make your heart race, leaving you with an eagerness and thirst to listen for more. Mary had a quality to her voice that was like no other. It was deep, throaty and sensual and from it sprang opinions and truths I’d never heard or read about. Revelations that brought clarity to the world and implemented an understanding and appreciation never imagined before. The talents she was endowed with, her affinity for the arts, her keen incisive wit, her indomitable intellect that shined through at party conversations and in her work. Those cute little notes she would leave and they were always found in a part of the day I needed them most. Her love of life and beauty, the constant energy she possessed and the inquisitive nature she used to express it; her worst day was a good day for me. She was the purpose I drew breath, the object of what I wanted. All that came to an end when she was killed. We went on a ski trip and were sliding along on the side of a mountain when an avalanche rolled down on us. I managed to stay above the snowline and quickly got free to look for her. I dug for what seemed like eternity with frantic tears staining the snow I tossed away. It was as if time stood still; only my hands and snow I shoveled seemed to move, and it moved in slow motion. Finally, I found her. It was too late. She was all crooked like her smile – only broken and lifeless. From that moment on, my life became an empty voyage. I see faces in windows watching me glide by. They all have eyes big with shock and their fingertips are covering mouths wide open with awe. A long line of cars snaked through the city streets and left people on corners watching it go by with that same dumbfounded look. Droves of folks came to pay their respects and the image the procession composed, with its stream of cars and headlights, was a testimony to how beloved Mary was. It was the blackest day of my life. Her funeral took place on a clear, sunny afternoon – another testimony. I carried a heavy burden after that. It had weight and substance, and it harnessed me in a dark cloak of grief. Hours slipped into days and days migrated to months while the daily drone that life produces swept me further from the sunny afternoon I said goodbye and the sharp ache I felt inside that day. Eventually I became trapped, locked in my own isolated prison. I had no family close by and all my friends belonged to Mary and myself. They were couples, and I was now single. It was a natural course of events for them to fade away in my life. By degrees, I was left alone with my thoughts and memories of Mary. I couldn’t bear living in the house I shared with her so I sold it and moved into a loft downtown. I hoped to change my life with a different lifestyle but found it was me who needed to change. Well over a year had passed since Mary was lost and the cloak of grief I wore had lightened, but it still had a haunting presence. That’s when I saw her. She was across the street in a neighboring apartment, and I could see her through my loft window, twirling around in a summer dress with a glass of white wine. Her gaiety and grace instantly reminded me of Mary, and when I looked closer I realized there were many more uncanny similarities. Her jet-black hair bounced around on white linen shoulders, and my heart jumped when I thought it was Mary. From that moment on I spent my idle time watching the girl in the summer dress. I would come home from work, turn out the lights and turn on some music, sit down in my big easy chair and look across the way toward her bright window. It was like my own personal television with one channel on the screen. The “Mary Is Alive” show. It wasn’t long before I bought a big brass spyglass – the kind a pirate would use. It sat on a tall brass tripod with long wide legs. That’s when I viewed her like I had a front-row seat. I could see her features, familiar to Mary’s - and like Mary’s, her green eyes danced when she laughed. There were times when I felt embarrassed and ashamed at what I was doing, but the sheer joy it made in my life would always counter those thoughts. Besides, what harm could it be if this private world where a tiny version of Mary existed took me closer to what I never lost, the love I felt for her. If it fabricated so much color in my life and it never really hurt anyone, how could it be so wrong? Each night I dropped everything to peer through my spyglass. I would observe this other world, one in which my beloved lived, and somehow breathe a little easier. I looked into the peephole and watched for hours like I was monitoring a snow globe. A tiny little world magnified by glass. I couldn’t hold it or shake it around, but I didn’t need the snowflakes to cast a spell on my view of that world. Then suddenly she was gone. I came home to find several men taking her furniture out the door. She moved. Moved and now vanished from my life. It was an unveiling that was too painful to live with. I walked around in a fog for days, my mind reeling from the sudden vacancy my existence now had and the banal subsistence I was relegated to. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep; the only thing I thought about was Mary. I had to find her again. My mind had been spinning with musings of her, until this morning when I woke up and the fog dissipated into one perspicacious assessment. I realized through a leap of faith I could join her. So I took the plunge. And now that I’m falling for love, I have no regrets. In fact, I’m ecstatic over the idea I’ll soon be with Mary. I know the love we shared will act as a compass to guide me to her. I know she’s waiting for me. I know we will soon be together for eternal bliss. Faces once again appear in the windows I fly by. They’re all aghast at my descent while their eyes watch me plummet to my end. Or beginning. The ground is coming at a faster pace now, and a multitude of faces are looking up at me while I fall. They look like baby birds waiting to be fed, their mouths open and necks stretched to see my landing. I can make out individuals in the crowd, and in the last seconds I’m able to find the girl in the summer dress. For a fleeting moment I wish I could thank her. My eyesight shimmies from the raging rush. The street before me has turned from a silver thread to a huge gray wall. It won’t be long before Mary and I… ©Rothya James Patterson

Another Vietnam Story by Rothya James It was the last cold breath of the Winter of 1966 when I started receiving the notifications. At first I ignored them, tossing the paper away with resolutions there must be a mistake. Maybe I thought that by crumpling the letter up in a tiny ball, I could somehow squeeze the urgency and finality the message these notes carried into oblivion. Finally, in the closing sighs of Spring, they warned me of incarceration and disgrace if I continued the folly of not responding. The last letter stated in so many black and white terms that I was to report at the local draft board. I was ordered to take a physical for induction into the United States Army or else. It wasn’t hard to imagine what the “or else” might encompass. My draft center, where I registered when I turned 18, was in Dallas, Texas. I was in Houston at the time, failing my classes at a small junior college. Fresh out of high school, I entered college without the slightest notion of what it took to maintain a successful run at advanced education. I was totally void of the self-discipline it would entail. For the life of me, I could not figure out how the blazes the draft board knew so quickly I had flunked out of college. I kept looking to the sky for some sort of surveillance flying above me. I would check behind each door I opened to see if a G-man was hiding there - so astonished was I by their proficiency at calibrating my availability for the private club they had and extending a little invitation to their party. I was an arrogant boy at the time, 19 or 20, with testosterone raging through my veins. It clouded all thoughts I might be able to muster at maintaining any facsimile of a sensible course. I was more interested in jaunts to Galveston, hanging out on the Gulf Coast chasing girls in bikinis. I would dash to the next party where free beer might be found or ride in a cool car on those breezy Houston evenings, looking for encounters with the opposite sex. My brain was full of witless dalliances such as these, rather than the pursuit of a future through education. I was stupid and boorish and practicing such irresponsibility could prove a fatal turn of events. One might end up in a green uniform with a rifle in hand, heading for a war called Vietnam. I knew nothing about foreign affairs or politics of that era. I had never even heard of a place called Vietnam. I was a silly, mid-Western young man that had no clue of what I was about to embark on. The only thing I was sure of was that thing whole thing – this summons by a faceless presence called the government – was definitely interfering with what I wanted to do: have fun, party, and declare this new independence I had discovered after leaving my parents’ home. It was not long after receiving that last letter before I found myself standing in a long line of bewildered boys. We were dressed in nothing more than our underwear as we moved from one table to another, being probed and inspected like cattle. There we were, standing in file - like so many bottles in an assembly line, dashing along a conveyer belt. We were tested and confirmed and passed on to the next stage of procedure. In those days if you could bend your arms and legs, walk and talk simultaneously, and read a chart of letters across the room, you qualified to carry a rifle in a combat zone. I, for one, was a healthy young American boy who could do all these things plus jump up and down as well. I qualified. When I look back on it now, I see it was a sign of the times – moving from station to station amongst all those glorious young bodies: all those hearty, untouched, immaculate new bodies. A person couldn’t help but wonder what the need for all this manpower might be for. One boy after another was being stamped on the rump with a good ol’ American seal. A free pass to potentially be sent off to a place that would do it’s best to cripple and maim those beautiful bodies. I stood with all these perfect bodies, and none of us realized we would soon be victims. Victims of stark, chaotic realities that would scar us all - if not the body, then certainly mar the soul. It never occurred to any of us that a few of our numbers would not return home. Weeks later, I was looking at a room with an American flag draped on a pole and posters of the United States Army hanging on the walls. Once again I stood with another batch of bewildered boys. A young second lieutenant had us all rise from our seats, raise our right arms, and swear an oath of alliance that would officially shuffle us off into the army. Before the day had a good start, we were all climbing on a bus bound for Fort Polk, Louisiana. Right off the bat, I was commissioned to be in charge of my mates. For some reason, I was considered an appropriate soldier for the task and given a manila folder from a staff sergeant that witnessed our little ceremony. The folder contained files on all the fellows and myself and left me in charge of the boys. I was responsible for making sure they all reported to get on the bus. I took the mission to heart and made sure everyone was there on time for the ride to be all that we could be. Waiting for us at the end of the bus ride were several men wearing Smokey the Bear hats. They seemed very upset and angry for some reason, while screaming orders and insults at an ear-piercing frequency. We all looked ominously out the windows of the bus while clambering off the vehicle into the fray these men had created. Instantly they demanded we jump down on all fours and give them twenty. After some moments of confusion, we came to know their meaning was push-ups to be counted out loudly while they continued their vocal assault on our arrival. I didn’t know it at the time, but these gents were to be our drill sergeants – the leaders in charge of us for the weeks ahead. They were the first introduction into this new venture called the Army, the very first people to greet us. I took note that no one shook my hand. Fort Polk was a dismal and desolate place, surrounded by uninhabited woods and swampy grounds. It was well into June by now, lending days and nights to be hot and oppressively humid. The only highlight I could measure in the earliest hours of my new home was the food: it wasn’t bad. Other than that, it seemed more like a prison yard than a United States Army post, with brutal guards and unreasonable rules. That first night, I laid awake in my bunk in the barracks I was assigned to, contemplating this whole affair I had gotten myself involved in. I could hear the rustlings and restless shifting of my fellow soldiers while I stared at the barracks’ ceiling. There must have been fifty or so of us in the sleeping quarters, and they too were probably harboring the same thoughts I had. We all lay in the dark together, scared and feeling lost, the stifling heat pressing down on our breath with no air conditioning to relax the room. A hot, muggy breeze drifted in through the open windows and settled in beaded sweat on all those flawless young bodies. Orientation was the order of business for the next few days. After breakfast the following morning, the platoon I was in, made up of all the guys in my barracks, were taken to the post barber shop. There we got the signature haircut that makes everyone look the same. That buzzed crewcut which signifies to anyone who looks at you – at least in the 60s it did – that you just got drafted. We all took our turns sitting in the barber’s chair and watching a big mirror while the barber, with no more care than mowing the lawn, dissolved our identities into buck privates. Afterwards, my buddies and I stood around outside the barber shop grinning foolishly at each other. We recognized the fact the lot of us had gotten one stop closer to becoming a United States soldier. We were beginning to look like one anyway. Shortly after that our drill sergeant led us to an elongated building where we were issued army uniforms. We all stood in yet another assembly line with a wide counter that equaled the length of the building. Individual stalls were set up where you received specialized pieces of the required ensemble. Green socks, T-shirts, and underwear were thrown at us to start with, and we were told to disrobe, take our civilian clothes off, and put on the army greens. The next stall gave us military boots, the stall after that had green fatigue shirts with “US Army” stamped on it. Then came green fatigue pants and a green canvas belt with a shiny brass buckle. The last stall had duffle bags to stuff our new wardrobe into and carry back to the barracks. It seemed we were all given garments that were a size too large, made of material that was way too heavy for the weather there. Needless to say, none of us were reveling in the green outfits or enthralled by it all. It wasn’t like we just walked out of a Fifth Avenue clothing store. After our uniforms were dispensed, we spent the ensuing days marching from one building to another, where we took psychology tests. Inoculations for exotic diseases one might come across in a tropical jungle were administered, and our numbers were asked general questions that would end up in personal files. All the army initially knew about us was our capability at toting a rifle. Now it was intent on getting to know how we ticked. I remember one table I came to where a corporal asked if I was a CO. I immediately pointed out I had just gotten in the army and was hardly the commanding officer. The young man chuckled and informed me he was asking if I was a conscientious objector. So ludicrous and ignorant was I to the issues of the time, I hadn't realized what the question embodied. Once the matter was cleared up, I moved on to another table with a sheepish grin on my face, hoping the army wouldn’t figure out what a dummy they had on their hands. The coming weeks were dedicated to obtaining the faculty and skill of marching in file as one unit. In a short time my platoon became very efficient at this, with a beat and rhythm that made our drill sergeant proud. Obstacle courses were used to pound us into shape, and in conjunction, the knowledge of how to use and take care of our weapons was exercised. There was a broad and sometimes brutish form of brainwashing that took place. A system that would whip us all into a mind-set a good soldier would need to become accomplished warriors in combat. It was a formula that was put in stone by the ancient Greeks, adopted and modified by our modern military. I find it fascinating that such a process is used today and set in motion from a time of the 300 Spartans. It’s a military regimen that has survived the ages and devised by the very same people who developed the idea of democracy. As we neared the mid-point of basic training, rumors were abound at getting out in the field and putting what we learned into action. It would allow us the opportunity to use the gear we were given and actually live the real thing, like sleeping in tents and eating C-rations. We would spend three or four days out in the boonies putting our newly attained abilities at being a soldier in play. Qualifying on the rifle range was one of the requirements. This was an important part of the field trip simply because if one should fail to qualify it meant repeating basic training, a dreaded and humiliating result. It was also a main part of the rumors. This would be a time a soldier could discover how to spot snipers on the sniper field and test his mettle in the tear gas chamber. During this event each individual would get a chance at tossing a live hand grenade, pull the pin and count to three before throwing it over a wall; another large part of the rumors. Everyone looked forward to it, and, at the same time, shrank from the fear of it by not being all that he needed to be. The day finally came and we all pulled our equipment together, marched out into the neighboring woods to a distant clearing and set up camp. Each of us had been carrying a rifle referred to as the M14. It was a heavy but reliable weapon with a wooden stock and a long barrel. The old timers had a fondness for the thing as opposed to the M16, a plastic stocked but lethal weapon I ended up using in Vietnam. It only weighed seven pounds with a fully loaded clip. A popular weapon today that can be found in any gun shop, the M16 was just being introduced in combat. It had a reputation for jamming if the soldier didn’t keep it clean. But the real love the old timers shared belonged to the celebrated M1. A standard issue weapon used by the GI in World War II you could drop in the mud and it would still fire. The M1 was trustworthy but could only be loaded with eight rounds. The M14 was easier to manage and had a twenty round clip for more firepower. This is the weapon I had along with my comrades to qualify on the firing range. I presume the reason was because of a surplus of the M14s at the time. They were used to be trained with while the manufacture of the newer M16s were sent overseas for combat. That night in camp, the platoon put up the one-man tents we were to sleep in along with the rest of the companies in the throes of basic training. The big evaluation of showing our marksmanship was scheduled for the next morning and all of us were nervous and somewhat tormented by it. After everything was in order we sat around wiping our rifles down listening to another rumor creeping through the ranks. Apparently one of the kids in the field got bit by a Coral snake and no one knew who it was or what happened to him. To this day I still don’t know the results of that occurrence or even if the rumor was true in the first place. I suspect it wasn’t. At any rate it made for a restless evening slumbering on the ground in our little tents. All night long everyone was positive a critter would scurry into their sleeping bag uninvited. The next morning we marched to a crowded firing range with countless young soldiers standing around holding their M14s. Drill sergeants were everywhere barking out orders, busy escorting one group of privates from the firing line and dashing another group in. They were transferring the bodies as rapidly and as efficiently as possible. It seemed like an endless state of affairs with a ticking deadline taxing the situation. The process was slow and tedious asking each shooter to fix his rifle sights for wind and distance before he was able to qualify. I stood by along with my platoon waiting patiently while the procedure moved at a snail’s pace. It struck me at the time of the sheer evidence the whole ordeal presented. Vietnam loomed on the horizon and all these young bodies were needed for something and it had to do with shooting guns. To qualify you just climbed into a hole about three feet in circumference and four feet deep. Laying your M14 on a couple of sandbags for support and setting the sights on your rifle one started popping paper targets. I noticed a forgotten set of foxholes down at the far end of the firing line that looked like remnants of a ghost town. It was easy to see things weren’t going well so a big drill sergeant took the initiative and hustled my platoon in the direction of the unused chambers. When I got to my hole the sergeant kicked the lid off and told me to jump in and make myself at home. I looked down at the pit and realized what we was asking me to do. Inside the cavity was a thick network of spider webs lacing every nook in the space with six or eight shiny black spiders dangling randomly in the webbing. It was obvious they had made themselves at home already. I could see they were full grown Black Widows and they didn’t look happy about being disturbed. I anxiously voiced a protest at descending into the hole but the drill sergeant would not hear of it. My guess is he figured if a handful of spiders were going to scare me off, what was I going to do with hombres shooting at me in the jungle. After futile complaints on deaf ears, I climbed down into the den, killed every spider I could find and started setting up my location to shoot. I ended up qualifying as a sharpshooter, a respectable mark. But I’m sure I could have qualified higher had I not been preoccupied with the thought of something crawling on me while I pulled the trigger. Toward the end of the field trip my platoon was taken to a small clearing deep in the thickets where a set of three wooden baseball bleachers were in the shape of a rainbow facing a blackboard. The platoon mounted the bleachers while a first lieutenant stood by watching us, standing in front of the blackboard slapping his left hand with a swagger stick. He was a dandy dressed officer in pressed and starched fatigues with black spit-shine boots that gleamed in the sunlight. Next to him was a table covered with canisters of assorted sizes and shapes. We all climbed to our seats with uniforms slept in for days and got ready for a lecture on the different types of gas a soldier might chance upon in combat. The seat I ended up in was at the lieutenant’s left, the bottom row with my feet on the ground at the inside spot beside the middle bleachers. Across the gap a foot away, on the bottom row of the middle section, sat a pimply-faced somewhat obese kid. He looked to be a bit dull and emotionless with his big feet planted firmly in the dirt. As the lieutenant began his discourse on useless information for battles in unknown jungles, the most important lesson I received during the whole time of basic training unfolded on the sandy floor of that clearing. And it came from the most unlikely of characters. From the flanks of the tall grass that ringed the clearing, a small creature scampered onto the sand, intent on getting across the terrain. He dashed straight for the lieutenant, traveling at a brisk pace as if it were trying to get away from something. I was mystified by the sight of it and quickly lost interest in what the lieutenant had to say. My attention focused on this tiniest of vagabonds. It was a velvet ant, a wingless wasp that looks exactly like an ant but huge in comparison, measuring about an inch long. They come in brilliant colors such as powder blue, sunset orange, emerald green, or scarlet red – and always bordered in black. I can count on one hand how many times I’ve seen those insects. They have a surface that seems to be made of velvet with shiny black eyes like tiny football helmets. Their long spindly legs appear to be black patent leather and the scarlet this one sported made me think of the English Redcoats from a forgotten age. Hot in pursuit were six pitch-black wasps that had a bright orange dot on their backs and large, smoke-stained wings with black veins. I’ve never seen wasps like these as they flew out of the woods in a V formation like they were coordinating their chase. Flying to the velvet ant like they had radar they immediately attacked him without reservations. Two of them flew ahead of his tracks and landed to make a ground assault while two others dove directly on him. The remaining two buzzed around in close circles as if searching for more of the enemy and acting as reserves. The tiny ball of insects grappled around in the sand for the duration of the lecture. The fight carried on with life and death ferocity while their abdomens pumped stingers at each other like jackhammers. All of them eventually joined in on the conflict and all fought valiantly. But the velvet ant, against all odds, overcame the onslaught and prevailed. I couldn’t believe how determined the ant was to survive, the countless hits he took from all the foes he battled. Finally breaking free from the melee, he made a beeline for my direction. In his wake were two dead wasps, two more struggling around critically wounded, and the other two flying errantly about confused by their location. He was getting away, taking the shortest route in hand, the gap between the bleachers I sat at. I silently cheered for him, so baffled was I at his bravery and the limitless endurance he expressed. Clear of the danger, he ran for his life and ended up in the divide just below me. I looked down at him almost in tears from the sheer joy of his victory. I was astonished and whimsically enamored by his achievement. Impulsively I tugged on the dull-witted boy next to me, pointing out the tiny hero. Without a thought, he swung over to grind the little bug with his big foot like he was putting a cigarette out. I was stunned. I just stared at the inane boy, not believing what he had done – concluding such a triumphant cause in such a dastardly way. I have no regrets in the two years I served my country. In fact I’m proud of it. I was assigned as a combat medic in Vietnam, earning a host of medals. Although it left me with some ugly memories, it also gave me great ones. There are memories of comradeship that I’ve never experienced before or since. I have memories of exotic places; beautiful places that to this day I see clearly in my mind’s eye. But most of all it gave me solid ground to stand on. A feeling of worth that has never been matched, giving me a foundation to live by from the meaning of duty and honor, integrity and character. Words seldom used by civilians. I think of that velvet ant from time to time as well. He demonstrated the fruitless results that war can offer. Those heated issues that seem so important to mortals are merely trivial pursuits held by a higher office up in the bleachers. He displayed what a soldier was. It wasn’t strutting around like a peacock slapping a swagger stick in the hand. It was dirty, hard, and perilous. He taught me perseverance and resiliency. To live life with a gutsy will. He showed me the strategy to never give up, never quit no matter what the odds. To find a way to survive and with it comes success. He also taught me one more thing. You never know when that big foot will come out of the sky and crush the life out of you. © Rothya James Patterson

Interlude by Rothya James “If you can guess what I have in my pocket, you can have it.” The homeless man sat on the park bench and waited for my answer. It was the same question put forth to me by the same individual on the same hour of the day for the last several months. his crystal blue eyes looked up at me with searching anticipation. There was a twinkle in those eyes and the only glimmer of what once was a handsome face on the leather, line-eroded mask he was now left with. A shimmering spark of long-lost youth that his emaciated body had to show from all the years of life lived. He looked up at me with those clear blue eyes, wearing a wry smile, waiting for my answer. Prior to this daily occasion my doctor advised me to take a thirty minute walk every day. I did so in this very park. And the path I chose took me by the park bench this homeless man sat on each day seemingly waiting for my arrival. it was a daily encounter I had grown to expect. Always coupled with the same phrase, “If you can guess what I have in my pocket, you can have it.” The walks started when my doctor diagnosed that I was a diabetic, a malady that came to me in total surprise and astonishment. I was not overweight; I worked out diligently and was in excellent condition. I spent a lifetime monitoring my diet. Observation of my health was so intense it could be classified as a fault. Yet here I was, on my scheduled walk. There seemed to be an epidemic of sorts plaguing our culture, and I was now swept up by this tidal wave of disease that was drowning our population. How in the world did I acquire diabetes? I was befuddled with the loss of an answer, and the only resolution I had was to take the advice of my doctor. Swallow my medicine and have my thirty minute walk each day. For the first time in all these hikes, I stood in front of the homeless man and mulled over his statement. I taxed the recess of my mind trying to figure what on earth could be in this forsaken man’s pocket and whatever it might be, what would be its worth. Perplexed by the dilemma, I finally looked down at him with a request, “Can you give me a clue?” His wry smile split into a grin and he quickly responded, “What in life can you count on?” I fingered the clue in my mind for a summary of moments, delving into the alternatives. Suddenly a rush of revelations came to me in one single word: “Nothing!” The old man’s wide grin turned into a cackle. In a flash of a moment he stuck his hand into his pocket and reached out to expose an empty palm. “Here’s your prize.” I viewed his vacant hand with my own brand of wry smile, then dug into my pocket and replaced the vacancy with a ten dollar bill. His head snapped up in wonder, “What’s this for?” “You got me buddy. Get yourself something to eat.” “I won’t get food with this.” “It’s your money; spend it the way you want.” “Thanks, mister.” “No thanks needed, enjoy.” “Thanks, I will.” I mused over his gratitude. “I guess I’ll see you tomorrow.” “May not have a riddle for you.” “Doubt if I have ten bucks.” With that, the old man started to cackle again. I spun around on my heels and walked away. As I continued my stroll down the path, the homeless man’s cackle faded into the trees. My thoughts of him lingered and a clarity of the experience evolved. I realized in my construction the message he inadvertently gave me. Life has no promise or guarantee, no rhyme or reason. It has nothing to offer but the adventure of life itself. There seems to be a string of episodes with no apparent arrangement, full of whimsical events and perhaps entwined in some grand plan; a fixture of a magical system. Setbacks should be expected because they are a part of the blueprint, and any prize you may win in life could be a disappointment. And sometimes you can come out ten bucks ahead. © Rothya James Patterson

League Play A Short Story by Rothya James I love baseball. I love how individual achievement interlocks with the play of the team. It’s the most perfect game ever devised. Where the losing team doesn’t run out of time, it runs out of opportunity. The one game with a natural ending, like a good book. I started playing American Legion Baseball when I was around ten in the 1950s. I played in the D League, and when I got old enough I went to C League, then on to B League. My dad was the coach of the teams, and as my buddies and I progressed through the leagues, we became city champs. My brother and I spend summers with Dad and our pals, and those wonderful moments couldn’t have been better. It was all so beautifully innocent: the hot afternoons, the teamwork and boys club comradery, the pursuit for baseball perfection. If we played hard and listened to Dad, we won. And we won a lot. When I got too old for the league, I was offered my very first job. I have no proof of this, but I suspect the employment came by way of my dad. The man that managed the league was good friends with him, and he was the same fellow that hired me to take care of the field and be the official scorekeeper. Every summer day I was back at my favorite spot on the planet: the ballpark. I would rake in the infield, the pitcher’s mound, and around the bases. I would lay the chalk down for the foul lines to the outfield and the batter’s box – then water the dirt to keep it in place. And when the games started, I’d have the greatest seat in the house: right behind the backstop in full view of the field, registering the hits and recording the outs. It was the next best thing to actually playing the ballgame. And in a way, I didn’t really miss those fabulous afternoons playing ball with my dad and my cronies. It became an extension of the mix, and it pacified the emptiness that would have surely grown had I not had the job. Each night after the games, I would call the local paper and give them a rundown on what took place. The scores and highlights; the top hitters and winning pitchers. Looking back it almost seems laughable that my ballgames and the results of them could be found in the sports page of the paper that next morning. It was a reflection of the innocence and sweetness of those times. The blissful simplicity. The uncomplicated decency that prevailed in the American culture then. It was a good time to grow up. My last day on the job was not unlike any other day. I spent the summer night with my customary snow cone I always enjoyed while sitting behind the backstop, measuring the details of each game. Spectators would drop by to find out if their kid got an official hit or what inning was in play. The routine of everything was the same. And as I recall, I see nothing extraordinary about that last day except for the fact it was my last day. That final day produced a milestone in my life that marked a transition from boyhood into young adulthood. At the time, I didn’t realize I would never be involved with organized baseball like that again. I played for my high school after little league but with different motives for the game. I played for the glory of a letter jacket and the notice of girls. But the games I played in little league was for the sheer joy of baseball and the marvelous friendships I experienced with the guys. The pride I felt for my dad being the coach. The memories I have of those games - some are so vivid, so clear in the retentions of my mind - I feel I can reach out and touch them, hold them. They’ve been like old friends in my life, and I visit them whenever I feel lonely or disenchanted. In my heart, it made a hero of my dad. And you know what? He still is. © Rothya James Patterson